Janie Paul Interview Continued:

JP:…talking about these issues was still miles away. It wasn't like it is now. People thought we were doing something really unusual. There were some other prison arts programs in operation. California had a long history with its program. There were various people but it was a very small community. We used to meet for these gatherings at the Blue Mountain Center in the Adirondacks for a number of years. It was a wonderful gathering of activists and people involved in prison arts. I had always hoped that it would grow and that people would be thinking more about issues of mass incarceration in the United States — and that has happened.

IOA: How do you feel about the way the Art for Justice Fund and other organizations have framed the issue of incarcerated artists?

JP: Agnus Gund’s Art for Justice Fund has framed the issues really well. There’s a spectrum of how political people are or not. There’s a way of critiquing capitalism and incarceration as it fits under Late Capitalism and its relationship to death and punishment, which is how I like to frame things. I think it’s really important that people see that the crisis we’re in has a history and is connected to the other forms of punishing poor people and punishing people of color in our country that have gone on throughout our history. Not all funding sources get that political. Some programs or efforts in prison arts don’t really go there. That’s okay — because people inside are still getting programs. But in our case, when my husband Buzz and I were teaching our classes, we had our students do a lot of reading about mass incarceration because we wanted our students, who are mostly privileged people, to really question how they situate themselves in relation to this crisis and to ask what will they do about it. And the art is the way we come together to be co-creators in a space.

Some programs use the word ‘rehabilitation’ which I don’t like to do., I don’t think we should use the word rehabilitation when talking about incarcerated people unless we talk about how our society needs to be rehabilitated. I also think that the word ‘crime’ — although we all use it — is a fraught word because we don’t use the word crime when we talk about our death penalty and the way people are in prison for long sentences— life sentences — and the way people have to live in prison. We don’t use the word crime for those phenomena but we do use the word crime for someone who sold drugs. We have to be aware that we are only using that word in relation to these people and not other people.

IOA: With respect to younger audiences who haven’t had much exposure to the idea of prison as a place where art could be created, how do you explain the value of prison art programs to them?

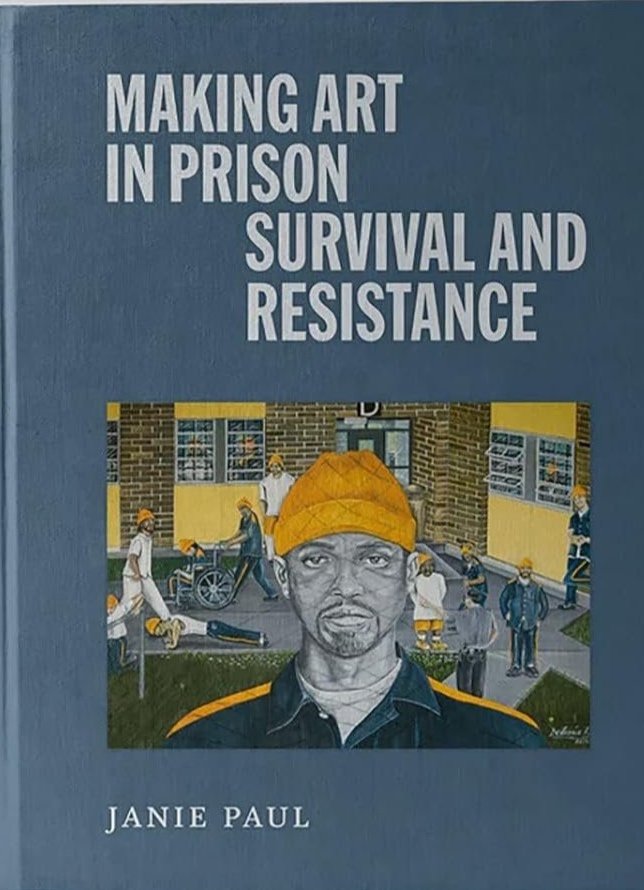

JP: Well, art in any of its forms is very valuable in prison. First, visual art is going on all the time in prisons around the country, whether or not there are programs. Because people are making cards, portraits, and tattoos. Art is flourishing in prison because it’s both a commercial venture and something that has relational value. For example, tattoos mark identity. So art is happening regardless of whether there are programs, The programs make that flourish all the more and add to the commercial venture. I just published a book about this. I see making art in prison as a kind of resistance.

People in prison need to find a way to settle into themselves. People always say “never call prison your home” yet in some way you have to create an area of comfort that’s home-like. One of the ways to do that is by creating the artistic sphere around you whether it’s in your bunk or your cell. With an art program, there’s a classroom. There’s a community where it’s a sphere of freedom and liberty. Facilities or teachers are there to help people develop and grow. Prison is about punishment, death, and destruction. Art is about growth, development, and having a future. So if you're serving a long sentence, the future is very grim. But if you’re making art, one piece leads to another and to another; each piece of art that you make opens up possibilities and opens up a future to you. So it changes time and it changes the future.

It also is a way of changing your role. Within prison you’re an object to be moved around, to be put in cages. People are put in cages, literally, when they’re transferred from one prison to another. An artist gets to become the subject, rather than an object, and that’s really important. You become the subject in relation to an object that you’re making. An ineffable thing, like music or dance, whatever you’re making, is an object that you cherish. That transformation from an object in someone else’s world to a subject in my own world — that’s very important. Also transforming anonymity to identity. transforming waste to value — as is the case with people who mix cultures out of waste materials. All these things are ways of humanizing oneself.

IOA: When it comes to artists experiencing re-entry, what do you think are some of the essential supports needed to make sure that they can continue making their art?

JP: Life when you get out of prison is very challenging. I know guy who got out after 40-plus years. He had so much trouble just getting his IDs, his Social Security card, his driver’s license, and a place to stay. So many people have challenges like that. In prison, you have the time to make art. You come out and you have all those challenges, plus finding a job. Many people find it difficult to keep making their art. At the Prison Creative Arts Project, we have The Linkage Project which provides community gatherings, workshops, exhibitions, and opportunities. I think belonging to a supportive community is very important.